In the past twenty years, Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) has become the best-known and most influential French writer. As a philosopher, as a novelist, as a playwright, as the author of filmscripts, as the editor of Les Temps Modernes, as a man who has never been afraid to commit himself to the moral and politcal as well as the literary life of his own times, he is unique. Not since Voltaire has Western civilization produced so humane, manifold, and bodly "engaged" a man of letters.

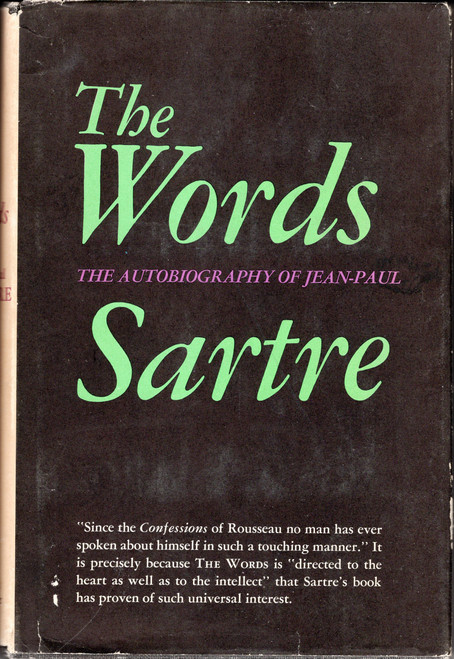

Sartre has undertaken his autobiography, bringing to his own childhood the same rigor of honesty and insight which he has applied so brilliantly in earlier books to Baudelaire and Jean Genet. "Directed to the heart as well as to the intellect," the result is like nothing else in the Sartre canon, and in France, where The Words has headed the bestseller list since its publication in January, it has already been accorded a place beside that other masterpiece of self-analysis, Rousseau's Confessions.

There have been child prodigies before, but few have been so blissfully happy as Sartre at 10. Born into a gentle, bookloving family (his second cousin is Albert Schweitzer), and raised by a widowed mother and doting grandparents, his childhood might be described as one long love affair with the printed word. Half a century later, he can write as passionately of his grandfather's library as Mark Twain could of the Mississippi River.

But ultimately, Sartre explores and evaluates the whole use of books and language in human experience. It was the great illusion of his life, he argues, that he grew up loving books, and taking it for granted that a courageous and productive literary career could do something positive on behalf of humanity's total struggle. If he eventually came to think otherwise, nonetheless his childhood joy in words, and his lifetime's commitment to their just and purposeful use, have remained powerful enough to sustain him.

"I write and will keep writing books; they're needed; all the same, they do serve some purpose. Culture doesn't save anything or anyone; it doesn't justify. But it's a product of man: he projects himself into it, he recognizes himself in it: that critical mirror alone offers him his image." --Sartre

About the Author